I have many enemies in my life. Microsoft Office. People that don’t indicate on roundabouts. The Taliban, I guess. The list is long. Longer than a Word doc you just added an image to that now has totally fucked formatting.

One such enemy are nutrition “experts” on social media. They’re everywhere now, because the only qualifications needed to be one are having an internet connection and being hot. If you have a Masters or Doctorate, all the better (don’t worry, it could be in English Literature for all we care, all that matters is you have the letters P, h, and D in your bio.)

You’d think that an information highway would be good for our education. Previously, you would’ve had to go to university or a library to learn specifics on nutrition science, but now we can learn it for free on the internet. However, the algorithm doesn’t reward boring old accuracy, it rewards things that stand out from the crowd. This means it’s difficult to build a brand off of common sense ideas like “Eat your vegetables”, and creators are incentivised to hold views that go against the grain - especially if it’s the sort of things that people want to hear, like “Eating vegetables is bad for you, actually”.

As a result, we now have a situation where people are probably more confused about nutrition than they were 30 years ago. There are some beliefs back then that I’d push back on, like the idea we need animal products to be healthy, but generally we had the right idea. Plenty of fruit and veg, and not too much junk. Now, however, we have people insisting that drinking unpasteurised milk is a good idea, or that we can cure all disease by eating nothing but steak. Our feeds are peppered with ‘fruitarians’ that look like they just left Stalingrad, and luminous red ‘roid heads overdosing on cow liver.

It’s funny at first, but tragic after some reflection. I’ve met people in real life that think vegetables or carbs are bad for them. People are literally dying because they got caught up in an online community that had bizarre nutritional beliefs, and couldn’t see the forest from the trees. Ordinary people aren’t going to read every study cited by someone on social media, and so we need to find some way of filtering the quackery from the genuine articles.

Mechanisms and Outcomes

Quacks know they can get more engagement if they find some piece of evidence that supports something unintuitive. Everyone has already been told they should eat spinach, and they hate it. What really gets their attention is if you say spinach is bad, and can say something science-y to back it up.

How do you do that, though, if spinach is in fact good for you? Well, the method quacks love to use is citing Mechanistic data instead of Outcome data. Mechanistic data is a piece of information that relates to some sort of mechanism, rather than a health outcome. I appreciate that definition isn’t particularly helpful as you could probably gather it from the names, but here are some examples to help:

Plants have defence chemicals that are bad for us.

Bioavailability of nutrients

[Insert Food] has some bad thing in it that’s tied to Cancer, Death, etc.

Notice that if someone is talking about the above, they’re not actually showing what happens if you eat the food they’re talking about. They’re showing some mechanism, like bioavailability, and extrapolating that a negative health outcome will result. The problem with this is that extrapolations are often wrong, and we shouldn’t glean confident beliefs from them.

Let’s take bioavailability for example. A lot of people online claim that plant protein is insufficient because it’s not bioavailable, meaning it doesn’t get absorbed by the body. They back this up with something called a PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score). If you look at the scores for different foods, you can see that animal foods score very highly, and plant foods do very poorly.

Not the dehulled hemp seeds! They’re my favourite kind!

After looking at this, you’d be forgiven for concluding we have to eat twice as many plant foods to get the benefits of eating animal foods. Social media influencers know this, which is why they keep talking about it.

Except, PDCAAS is not as useful a metric as it’s made out to be. The score is calculated by identifying the amino acid in the food with the smallest proportion (known as the limiting amino acid), and multiplying that proportion by digestibility. This means PDCAAS penalises plant foods for having a smaller amount of one amino acid, even if the whole diet includes other foods that evens things out. There are also some other problems with it that I won’t get bogged down with, because there’s a much better way to determine if plant proteins work - we can just look at what happens when people eat them.

This is why outcome data is so much better than mechanistic. It doesn’t matter how compelling a mechanism you cite, if you’re using it to justify a belief in some health outcome, and that health outcome doesn’t obtain, your belief is just wrong. If PDCAAS says protein can’t be absorbed from plants, but we find that people can build muscle on plant foods just fine, then I guess PDCAAS missed the target somewhere. Which is exactly the case.

Using mechanistic data is like trying to determine how tasty a meal is by looking at it’s ingredients list alone. Sure, you might get some inkling, but you know the best way of finding out? Just eat it and see what happens! Holding onto mechanistic data in the face of incompatible outcome data is like saying “Look, I know this lasagna tastes great, but it has oregano in it and I hate oregano, so it actually tastes bad.”.

Social media quacks love talking about mechanistic data because it’s easy to find some that supports any old view. This is why you see them talking about things like a specific chemical in oatmeal that’s linked to cancer, instead of just talking about what actually happens when you eat oatmeal. The outcome data disagrees with the narrative they want to spin, and so is conveniently omitted.

Ideology

A lot of social media influencers are, at least in part, motivated by some ideology. Now, ‘Ideology’ is a bit of a dirty word, and so that might be enough to turn someone off immediately. However, there are a lot of things that could be called an ideology that I have no problem with. Belief in the scientific method, opposition to bigotry, people that don’t wear headphones on public transport should be shot, etc.

The problem isn’t really Ideology per se, but following it over evidence. There are a lot of vegan influencers that are guilty of this. There are many animal products that aren’t good for us. It’s pretty much settled that processed meat and red meat cause heart disease. However, there are some animal products that seem perfectly fine (like low-fat dairy or fish). Despite this, a lot of people online make it out as if being in the same room as an animal product will kill you. They won’t. There are plenty of other good reasons to stop eating animals, but fear of skimmed milk powder in a Dairy Milk isn’t one of them.

This is a handy way of spotting someone who cares about being accurate over fitting a narrative. If I’m watching a video of someone that is in favour of animal rights, but they say that low-fat dairy is fine for you, they’ve just shown to me that they’re capable of seeing things for what they are instead of what they want them to be. Of course, it would be very convenient for vegans if literally every animal food was poison, but they aren’t, and the ones that claim they are lose credibility.

Nature Lovers

Quacks have a weird obsession with what’s natural or ancestral. The idea is, if we can just eat the exact way we evolved to eat, we’ll have solved nutrition science for good. These are the people that go hunting shirtless, and violently puke when they see a food has more than 3 ingredients in it.

There’s a couple of problems with this way of thinking. First, there are plenty of things that are naturally occurring that are really bad for you, and plenty of man-made chemicals that are great for you. Cyanide can be found in the woods, and B12 supplements are made in factories. The origin of a food really says nothing about how good it is for us. Again, we should just look at health outcomes instead of throwing food in the bin because it has ‘chemicals’ in it (all food is chemicals by the way, that’s just what stuff is made out of).

On the ancestral front, it’s relies on an assumed premise that’s bonkers - the idea that our ancestors ate what’s best for health and longevity. Why think that? Our ancestors ate whatever they could get their hands on. They shat in the woods, wiped their butts with their hands, and ate a 3 day old rabbit corpse they found in a ditch. Hardly dietary role models.

“But we evolved eating this food!” people say. Except Evolution doesn’t select for long term health, it selects for living long enough to have a kid and raise them - which 100,000 years ago was like 27. We weren’t living long enough to die of heart attacks back then, and so evolution wasn’t taking that sort of thing into account. We shouldn’t look to our ancestors for inspiration on nutrition for the same reason we shouldn’t look to them for medical advice. The mere fact that people survived eating a certain way doesn’t say much about whether or not it’s optimal. You know what does say a lot? Science! Maybe it’s better to pay attention to that instead of getting our shopping lists from cave drawings.

A Piece of Advice

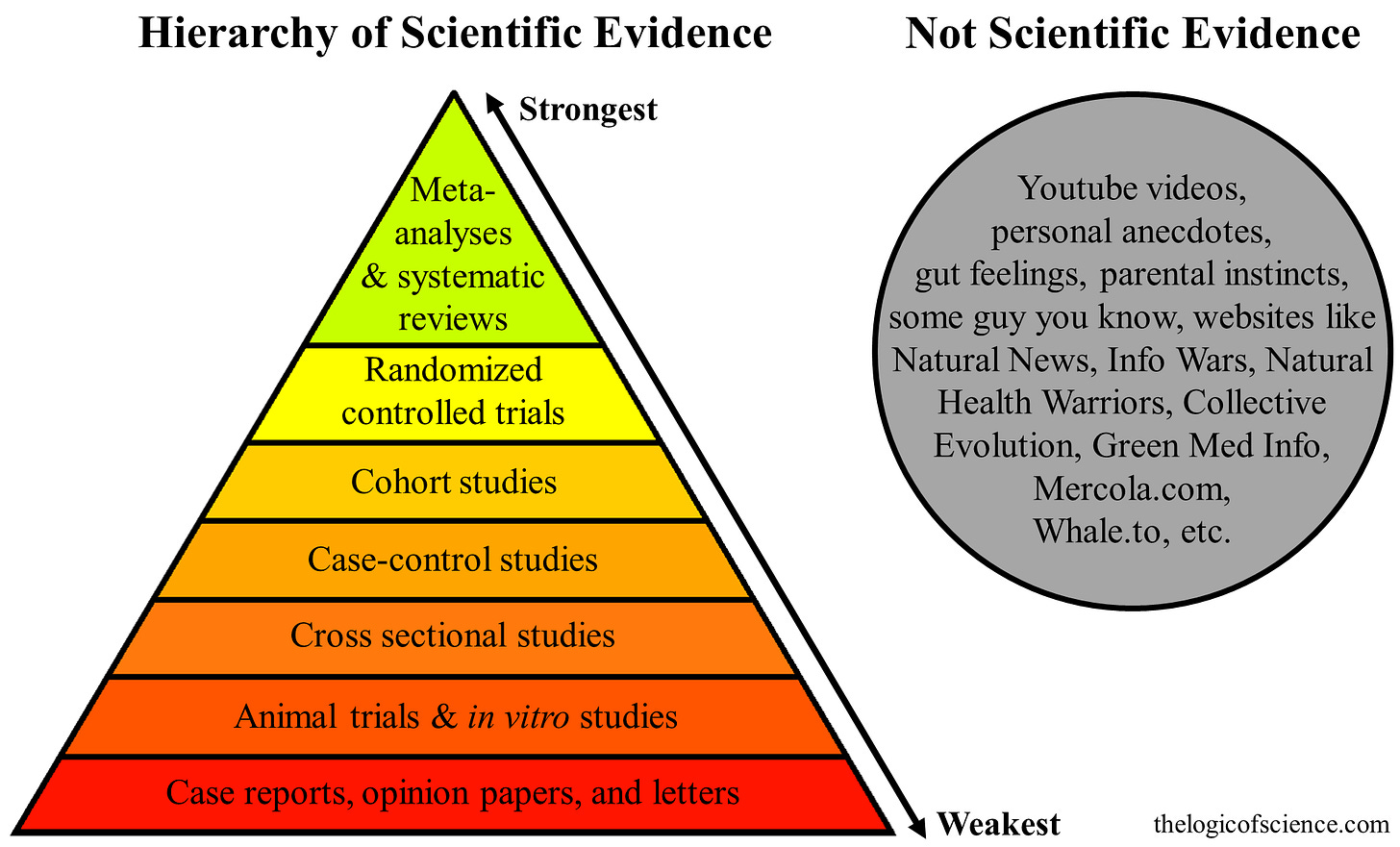

Quick one to finish on. This is the Hierarchy of Evidence. It’s used to determine how much weight we should give different pieces of evidence. The higher up the pyramid, the more conclusive.

Mind Meandering should be at the top, but weirdly no Google images included it.

Rather than go into detail on each of these options, let me give you a piece of advice. If someone is making a nutritional claim and they cite a meta-analysis or randomised control trial, it’s at least worth paying attention to (although I would read the source before believing anything). It’s not as if anything below that is totally useless, but we shouldn’t build really strong beliefs off them.

The name of the game is skepticism, especially for things that strike you as weird or counter intuitive. Remember, people make money from telling people what they want to hear, because then they can sell them snake oil supplements. My advice is believe the common sense things that have stood the test of time:

Eat wholegrains

Eat plenty of fruits and vegetables

Don’t eat loads of saturated fat

Exercise, drink less, don’t smoke, etc.

Anything that veers too far away from this should ring alarm bells and (unless it’s backed up by some serious evidence) should be ignored. That’s how you avoid finding yourself eating nothing but watermelon for a week, or serving up unseasoned bull testicles to your wife on her birthday.

100% of people who drink water in their lives have died. And 100% of people who developed cancer have drunk water. That's solid proof right there that water is in fact bad for you. Illuminati confirmed.

The top of the evidence pyramid is news articles about studies that prove that coffee is good for you.